Illustrating the truism that “the boss is the best organizer,” Rutgers University’s system of corporate governance, combined with its negligent response to the COVID-19 public health crisis, has energized a new spirit of wall-to-wall organizing among its workers. A coalition of nineteen unions has come together to fight the brutal austerity measures that resulted in job losses of over 5 percent of the university’s workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. To make matters worse, in a deep blue state with more resources than many others, Rutgers continues to lay off whole segments of its workforce, despite the restoration of its state funding in October 2020. The events at Rutgers are an important and underreported story, not only for the state of New Jersey but also for higher education throughout the United States. While the extreme austerity imposed at Johns Hopkins University, Ohio University, and the Kansas university system has received extensive coverage, much less has been written about the new kinds of labor and community activism that the COVID-19 crisis has catalyzed at public-sector institutions like Rutgers, which is one of New Jersey’s largest employers.

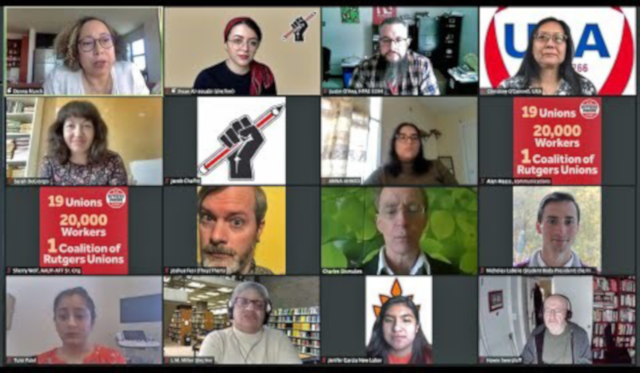

A broad and inclusive labor movement is growing in the alma mater of Paul Robeson—one that is economically diverse and community-based, built upon principles of equity and fairness encapsulated in the slogan “bargaining for the common good.” Inspired by the West Virginia, Chicago, and Los Angeles teachers’ strikes of 2018‒19, twenty thousand unionized faculty and staff have joined forces in the Coalition of Rutgers Unions (CRU) to fight for a new type of university that prioritizes teaching, research, community engagement, and worker safety over corporate governance, real-estate development, and the expansion of upper-level administration.

The unprecedented pain and disruption caused by COVID-19 has helped create a united front of unions that would have been unimaginable before the pandemic. Workers across the sector are advocating for a compassionate and common-sense response to the pandemic that insists on holding the line on layoffs until the end of the fiscal year 2022; providing graduate student workers—who are essential to the teaching and research mission of the university—funding to make up for the time lost toward their degrees; rehiring part-time lecturers who lost their jobs; and providing free COVID-19 testing at sites on all three Rutgers campuses (Camden, Newark, and New Brunswick). As the coalition fights for these bare-bones, subsistence demands, the shocking income disparities between managers in the central administration and the thirty-thousand-person-strong workforce is one of the biggest sources of contention. Rutgers’s top 312 administrators make more than $65 million dollars a year, and they have paid themselves average raises of between $10,000 and $12,000 annually over the past three years. This outrageous wage scale, combined with the proliferation of managerial positions, has led to a 21 percent increase in administrative costs between 2017 and 2019. Meanwhile, the lowest-paid workers—many of whom were making less than $40,000 annually—were laid off by the hundreds.

In spring 2020, Rutgers University was in the national spotlight when the US Food and Drug Administration expedited approval for a rapid-response saliva test for COVID-19, developed by Rutgers researchers, that promised to revolutionize testing and tracking of the virus. The technology also promised to bring enormous revenues and prestige to the university, as well as a likely boost in enrollments. For Rutgers’s workforce, however, this hopeful moment was eclipsed by the administration’s callous mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis closer to home. In April, outgoing president Robert Barchi laid off 20 percent of the school’s adjunct professors—known at Rutgers as part-time lecturers, or PTLs—by directing departments and chairs to not renew their contracts for the fall semester. These abrupt nonrenewals represented a devastating blow to undergraduate education, because PTLs teach at least one-third of the classes on all three campuses, including some of the largest survey courses in the sciences, humanities, and professional schools. Ironically, the university generates massive tuition revenues through the work of poorly paid adjunct faculty members. Equally troubling, the administration threatened over half of the maintenance staff with layoffs, along with close to a thousand dining-hall workers, many of whom were low-paid women of color.

Becoming unemployed took on a whole new meaning as COVID-19 ravaged the New York‒New Jersey metropolitan area in spring 2020, making it the global epicenter of the health crisis. Workers and their families confronted the loss not only of their jobs but also of their health insurance. These stark realities were made even more distasteful by the minuscule salary reduction that Barchi offered to take, as the president and top administration officials offered meager cuts of 1 to 3 percent in their annual salaries.

Disregard for worker safety accompanied the mass layoffs. Remarkably, as the pandemic closures swept the country in early March, Rutgers’s upper-level administration excluded all union representation from its COVID-19 taskforce. Without any worker voices, the taskforce insisted on keeping the university’s libraries open even after classes had been moved online. Although it remains unclear why this decision was made, many have speculated that administrators feared that closing libraries would buttress student requests for partial tuition refunds. In response to this callous disregard of worker and student safety, library staff and faculty members organized a sick-out and turned to union leadership for support. Rutgers AAUP-AFT president Todd Wolfson and vice president Rebecca Givan argued that keeping the libraries and other nonessential facilities open posed “an imminent danger to the health and safety” of workers, students, and the communities surrounding the university. The faculty union leadership demanded that Barchi immediately shut down the libraries on all three Rutgers campuses. When the president refused, Wolfson and Givan reached out to the national leadership of the American Federation of Teachers, who approached the governor of New Jersey, Phil Murphy. On March 21, the governor ordered the closing of all municipal, county, state, and college and university libraries. His executive order specifically referred to the closure of computer labs, which the library leadership had mentioned as a reason for keeping libraries open. By the end of May, it was clear that the union’s public health concerns were prescient; New Brunswick had one of the highest rates of COVID-19 in New Jersey.

The Rutgers administration’s privileging of financial concerns over safety extended to Rutgers health-care workers themselves. In the first months of the pandemic, the university’s medical residents, nurses, and other health-care staff faced ongoing shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). Rutgers medical resident Michael Gallagher described conditions in a Veterans Administration hospital in Hackensack, just across the border from New York City, where shortages became so dire that medical residents had to use the same N95 masks for three days in a row. “The university dragged its feet for procuring PPE for hospital affiliates and passed the buck to others,” Gallagher argued. This situation was all the more disturbing because he and his colleagues worked in some of the most vulnerable frontline hospitals at the epicenter of the COVID-19 crisis. Moreover, they also traveled from facility to facility, which increased risks for both them and their patients, given Rutgers’s failure to ensure that they had proper equipment. When the residents’ union, the Committee of Interns and Residents (CIR), pressed the university to provide an inventory of the available PPE as required by law, the university refused to respond. Many of the residents in the CIR were infuriated at Rutgers’s clear indifference and lack of transparency, which led them to organize with other medical-care unions, including the Health Professionals and Allied Employees, Doctors Council (an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union), and AAUP‒Biomedical Health Sciences of New Jersey. Gallagher himself became infected with the virus and was forced to quarantine just as the number of COVID-19 cases began their deadly ascent. By the end of May, he had not received hazard pay, nor had his fellow medical residents. They turned to Rutgers’s Office of Academic Labor Relations for redress and to the cross-union organizing efforts of the Coalition of Rutgers Unions. In the coalition, frontline health-care workers stand side by side with academic instructors, graduate student workers, and all kinds of campus staff, building a broad understanding of the university’s disregard for the safety and well-being of its workforce.

History of the CRU

The Coalition of Rutgers Unions solidified in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, but its roots stretch back over two decades. In the early 2000s, Patrick Nowlan, executive director of the Rutgers faculty and graduate student employees union, laid the foundation for the CRU when he helped establish three new entities: RutgersOne, the Rutgers Progressive Alumni Network, and a loose coalition of faculty and staff unions. RutgersOne provided an organizing space for undergraduates, strengthening campus social justice organizing and linking it to organized labor on campus. Similarly, the alumni network created a channel that brought together students and alumni across generations and allowed alums, many of whom had been activists as students, to stay involved in labor and student struggles. In this early period, the coalition of unions functioned as a loose network that centered primarily on sharing information and trying to coordinate contract cycles. All of these components proved important to forging the union’s imprint as a social justice union and later informed its participation in the cross-union organizing drive.

In the succeeding years, several structural changes strengthened both Rutgers AAUP-AFT and the coalition of unions. In 2005, under history professor Rudy Bell’s leadership, the AAUP chapter affiliated with the AFT, which injected new resources into the faculty and graduate student union, allowing for the hiring of four additional staff members. With the AFT came legislative and bargaining support, resources for research, and, very important, dedicated organizers for the part-time lecturers and for postdoctoral fellows. The AFT also allowed for greater coordination with the other Rutgers unions, including the Union of Rutgers Administrators, which organized as an AFT local.

In 2013, Rutgers incorporated seven out of eight schools of the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey in the largest public higher education merger in history. This transformed Rutgers into a university with more than sixty-five thousand students and a $3 billion budget. It also had important implications for organized labor on campus. The merger meant that as two sprawling institutions with many different unions came together, the AAUP-AFT could provide the glue, with 70 percent of coalition membership sharing either the AAUP or the AFT affiliation. The restructuring, which was done with minimal state funding, was opposed by a number of different progressive factions in Rutgers—largely because of its exclusion of University Hospital in Newark, New Jersey’s only public hospital, from the medical school, which left it vulnerable to privatization or closure. Despite the problems with the merger, it nevertheless created an opportunity for broad, cross-sector organizing. Health Professionals and Allied Employees brought another three thousand workers under the banner of the AFT and would ultimately play a crucial role in the CRU.

In 2015, Rutgers AAUP-AFT, the largest of the CRU unions, became more consciously involved with radical social justice and intersectional unionism centered on race and gender inequities. The union leadership’s understanding of social justice unionism changed over time. In the earlier years, it centered primarily on tuition maintenance or reduction through actions like Tent State, where students, faculty, and staff set up tents and built an alternative university, as well as on student-led initiatives such as Coke Off Campus and Students against Sweatshops. However, toward the close of Barack Obama’s second term as president and following the election of Donald Trump, Rutgers AAUP-AFT took a pronounced leftward turn and began to organize around the most pressing issues of the day, including antiracism and gender equity. A stylistic change also took place, as the union chose a black fist holding a pencil on a scarlet red backdrop as its logo. Former Rutgers AAUP-AFT presidents Deepa Kumar and David Hughes played a leading role in this evolution as larger numbers of faculty members of color joined the union’s executive council and the union experienced significant overall growth in its membership. Rutgers AAUP-AFT fought against the Muslim ban, the scrapping of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, and other attacks during the Trump era by joining in solidarity with our students and community groups. This approach galvanized and energized members, who came to see the union as a space for social justice activism. The staff was expanded to include four new positions, with a greater focus on organizing.

Most important, Rutgers AAUP-AFT set out to create a shop steward or department representative network that became the backbone of strike preparation. At the time, as the Janus v. AFSCME case got closer to the Supreme Court, public-sector unions were aware that they would likely lose the ability to collect agency fee from nonunion members to cover the cost of representation. It was therefore more important than ever to build membership and to increase the engagement and mobilization of members to prepare for a strike and to withstand the potential attack of the Janus ruling. All of these factors—the focus on members’ concerns off campus as well as on, the emphasis on organizing and activism, the growth in membership, and the active core committed to taking the union forward—played a part in Rutgers AAUP-AFT’s successful contract battle of 2019. Members voted overwhelmingly to go on strike. On the eve of the planned strike, the union not only won significant gains on traditional bread-and-butter issues but also achieved some of its social justice goals, including a groundbreaking program for faculty to secure equal pay for equal work along lines of gender, race, and other protected categories across Rutgers’s three campuses–a historic first that has set a precedent for other higher education unions. In important ways, the struggles and successes of the union laid the foundation for the CRU to come together and aspire to achieve even more.

Outreach to the community beyond the campuses was essential, because the CRU’s approach is based on the model of bargaining for the common good (BCG), a new strategic tool of the labor movement that emphasizes that workers are also community members. Forged in a time of declining unionization, BCG expands collective bargaining beyond bread-and-butter unionism to consider how workplace organizing addresses the needs of the larger community. By incorporating these concerns into labor organizing, BCG uses worker power to force employers to act in ways that benefit their surrounding area. One of the best (and most successful examples) is how teachers unions in Los Angeles and Chicago fought to have a nurse and a counselor in every school. More recently, the Chicago Teachers Union has also incorporated demands for affordable housing into its bargaining. In a time of neoliberal privatization and destruction of public goods, BCG focuses on expanding the public sector; it also undercuts the resentment against unionized workers by those with lower pay and fewer benefits. By collapsing the wall between unions and the larger social world, BCG is a powerful strategy for fighting the antilabor climate of the last four decades.

Rutgers’s social justice unionism has been on display in the handful of demonstrations held in New Brunswick since the pandemic began. In April 2020, a colorful procession through the streets called attention to the slogan “Rutgers Must Protect the Most Vulnerable.” Signs for the car caravan featured an image of a protester wearing a surgical mask and a Panama hat with a fist raised in the air—a signal of a new spirit of labor militancy. More than 150 cars joined the procession as it made its way from an abandoned Sears parking lot to the president’s mansion, which was shielded from view by a veil of trees and a recently rebranded sign “RevolUtionary.” When the unions returned to the streets again in late September, the masked marchers demanded not only that Rutgers administrators stop the layoffs but that they abandon plans to demolish a predominantly Latinx elementary school in the heart of New Brunswick in order to build a new medical facility. This alliance between the CRU and the broader New Brunswick community has developed over time. Both the CRU and the community fighting to stop the closure of Lincoln Annex Middle School recognized that they have the same adversary, Rutgers University, and therefore they needed to work together. The protest in September was a critical first step in establishing a broader, united front connecting university workers to the communities where they labor.

The CRU in the Era of COVID-19

From the start, leaders across the coalition recognized the pandemic as both a serious threat and an opportunity to build a broader base of worker power at the university. They anticipated, based on previous experiences, that Rutgers’s decision-makers would attempt to make the most vulnerable—disproportionately women and people of color—bear the brunt of the crisis. Administrators indicated early on that they would exploit the crisis to reorganize and “discipline” the workforce, following the pattern that Rutgers faculty member Naomi Klein has called “disaster capitalism.” Management at universities used the pandemic as an excuse to restructure and downsize the workforce.

At the same time, the unions recognized that, by responding to the crisis with an alternative strategy that protected the vulnerable, they could forge a deeper sense of solidarity across their diverse memberships. Dozens of union leaders across the coalition began meeting weekly to work out the details of a worker-led response to the pandemic. They called their plan a “people-centered approach,” stressing that the Rutgers administration has exaggerated the severity of its budget shortfall. Last spring, after warning of plummeting enrollment and state funding cuts, the Barchi administration estimated that the deficit for the 2019–20 academic year would be upward of $200 million. In reality, enrollment stayed stable and even grew somewhat, the state reversed threatened cuts and maintained full funding (thanks to a CRU lobbying campaign), and Rutgers is getting one of the largest disbursements of federal relief aid of any university in the country. The final shortfall for last fiscal year was well under half of Barchi’s estimate, and there is every reason to believe that similarly worrisome projections for 2021 are also inflated. Rutgers’s management strategy—running the school as a profit-making corporation—leads to brutal forms of austerity as the central administration protects unrestricted financial reserves and attempts to drive down labor costs at the expense of the core functions of the university: research and teaching. Sadly, Rutgers is not alone, as this has become the predominant approach to university governance. It needs to be fought head on.

The unions developed their own strategy for an alternative approach. They did not deny that Rutgers faced a serious financial crunch. Instead, the CRU came up with an innovative solution: a work-sharing program that would have allowed the university to save well over $100 million through furloughs, while protecting the incomes of all workers by relying on federal aid in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, passed in March 2020. In effect, the CRU proposed to take advantage of both New Jersey unemployment law, which provides jobless benefits for furloughed workers in approved work-share programs, and the federal unemployment supplement of $600 per week included in the CARES Act to make sure that workers didn’t lose any income. This work-sharing program would have saved Rutgers as much as $140 million through the end of July, when the CARES Act provision expired.

This concept of work-sharing (known as Kurzarbeit in German) comes from Europe. The idea is that during a period of financial distress, the employer and the state together share the salaries of workers, keeping them whole while creating savings for the employer. This arrangement differs from a traditional furlough program, since workers do not lose a percentage of their salaries. The CRU calculated that workers across the university could furlough at 10–60 percent of their time and all employees earning less than $350,000 would be kept financially whole thanks to the combination of state and federal unemployment benefits.

In exchange for accepting furloughs under the work-sharing program, the unions had a series of simple demands that were meant to offer an example of how a public institution like Rutgers should respond to a crisis. The central demand was no layoffs during the pandemic. Along with this concession, unions called for the rehiring of the PTLs whose contracts were not renewed for the fall under Barchi’s orders and a one-year funding extension for graduate workers whose research was adversely affected by the pandemic.

The work-sharing proposal was a perfect illustration of the two key principles in the CRU’s people-centered approach to the pandemic: protect the most vulnerable workers during a crisis and forge solidarity across the diverse workforce at the university. From April through June, the CRU met with the administration multiple times to finalize this ambitious proposal. Ultimately, though, the administration refused to make a deal. Union leaders suspect that they were advised on this decision by the law firm Jackson Lewis, well-known for advising university administrators across the country on how to break campus unions. Jackson Lewis had been hired previously by the Barchi administration. The firm’s list of clients includes Pfizer, Target, and the Exxon Mobil Corporation, and its higher education division has been hired by the University of California, the University of New Mexico, the University of New Hampshire, Barnard College, Columbia University, New York University, and many other colleges and universities. Jackson Lewis’s legal services are expensive—and the firm is notorious for perfecting the corporate strategy of bargaining unions to a standstill.

After rejecting work-sharing, the Rutgers administration continued with their profit-centered approach to the pandemic. The number of laid-off workers now stands at well over one thousand, nearly all of them low-wage workers who are disproportionately women and people of color. In June, the Rutgers administration declared a “fiscal emergency,” so that it could cancel the raises of the remaining union workforce. It then threatened several staff unions with further layoffs in order to force them into accepting furloughs on the university’s terms, with no protections against lost income or future layoffs.

While the threat of mass layoffs did enable the university to force several staff unions into bad deals, this did not break the coalition as some had expected. The glue that holds the coalition together is solidarity and a belief that the many different workers at Rutgers—food-service workers, graduate student workers, groundskeepers, doctors, adjuncts, administrative staff, nurses, full-time faculty members, custodial workers, and many others—are in this fight together. Among the leaders of the coalition, there is a shared recognition that unions must stand in solidarity with the most vulnerable, because an injury to one is an injury to all.

Paul Robeson once said that “freedom is hard-bought,” and so it is with building unity and solidarity through conscious and methodical effort. For example, because of the nature of their labor, many faculty members do not automatically think of themselves as part of the same workforce as dining-hall workers. But while faculty are obviously indispensable, so are the many thousands of other workers who make our colleges and universities run. A growing belief in worker solidarity, nurtured by Rutgers’s broad union coalition and coupled with an understanding that accountants and bureaucrats cannot run our universities, prompted leaders of the CRU to discuss establishing a worker and student council at Rutgers. This deliberative body would be made up of representatives of the seventy thousand students and thirty thousand workers that comprise the university. It would fight for a university that centers the core mission of higher education institutions: teaching, research, and service both to the profession and institution but also, importantly, to the communities where Rutgers resides. The vision of a Rutgers student and worker council is a political horizon toward which the CRU can strive. In the meantime, however, the CRU is a success story, despite the many challenges it still faces, because it has pressed all workers to act in solidarity—and it has asked the most secure and best paid among them to use their privileges to support less secure and lower-paid workers. These are the principles at the heart of our people-centered approach to the pandemic. They are central to the model of bargaining for the common good that unions at Rutgers have adopted in the present—and to the vision it is forging of what a public university of the twenty-first century can be.

The cross-union coalition is an important tool in fighting for a truly public university. However, during this unprecedented crisis in higher education, a broader strategy is needed that links together colleges, universities, and union and union-aligned workers across the country to make claims on the state. The New Deal for Higher Education provides this framework. At Rutgers, we need a New Deal that would significantly increase state and federal funding, with strings attached that encourage structural change in the whole university system. First and foremost, state funding should contain layoff protections for all workers, requirements to rehire the more than 1,500 people who have lost jobs during the pandemic, funding extension for graduate workers, and a mandate that contingent PTL positions be transformed into full-time jobs with benefits and academic freedom protections. Other important transformational issues include reduction of tuition (and, ultimately, free higher education for all New Jersey residents); unionization of the remainder of Rutgers’s nonunionized workforce; and elimination of racially discriminatory budget practices that disadvantage the Camden and Newark campuses. We should require that state funding be used toward the core missions of teaching, research, and community service. To enforce this, Rutgers would have to agree to transparency measures for how public funds are spent and to increasing shared governance within its workforce.

Another essential part of the New Deal for Higher Education that is needed at Rutgers and other universities throughout the United States is a roadmap for reversing the rapid growth in upper-level management. Of all the necessary substantive changes, this is perhaps the hardest to achieve, because it entails convincing senior administrators to cut the positions from which they benefit the most. At Rutgers, one in every seven dollars generated through tuition, grants, and other sources ends up with the central administration. Meanwhile, “responsibility-center management” has been imposed on the rest of the university, forcing individual departments to inflict cuts on themselves in order to balance their budgets while denying them a say in how the tuition revenues they earn are spent. The COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating, but the New Deal for Higher Education, not unlike the federal programs for which it is named, affords us a unique opportunity to provide essential resources directly to workers and young people, guaranteeing them the future they deserve.

Donna Murch is associate professor of history at Rutgers University, where she serves on Executive Council of the Rutgers AAUP-AFT. She is the author of award-winning books Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, and Assata Taught Me: State Violence, Mass Incarceration, and the Movement for Black Lives. Todd Wolfson is associate professor of media studies at Rutgers, where he serves as president of Rutgers AAUP-AFT. He is the author of Digital Rebellion: The Birth of the Cyber Left and coeditor of The Great Refusal: Herbert Marcuse and Contemporary Social Movements and the forthcoming The Gig Economy: Workers and Media in the Age of Convergence.